Cultures across the world have their own, unique baby naming ceremonies, ranging from simple to elaborate rituals to mark a joyous event in the family.

In Greece and Ireland, for instance, babies are often named after grandparents from both maternal and paternal sides. Often, babies are also named after saints belonging to the Greek Orthodox Church, thus, making the day similar to a birthday. Among Hindus in India, horoscopes come into the picture and zodiac constellations are assigned certain letters and phonetic sounds as ideal names for the newborn. In Bali, children are named according to the order of their birth.

A common thread in the naming ceremony across cultures is the shared belief that names reflect the baby’s personality and not just the gender.

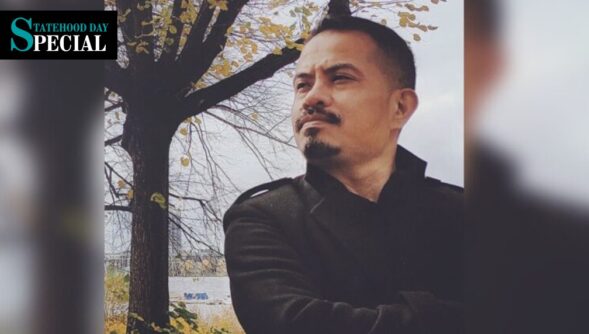

The Khasi culture is no different in terms of an elaborate baby naming ceremony and boasts of a rich philosophy behind the names. Speaking to noted author, Bijoya Sawian, opened up the world of ka jer ka thoh.

In her own words, “The naming ceremony is referred to as ka jer ka thoh. Jer means, “to name with an accompanying ritual” and thoh refers to the marking/smearing of the pounded rice solution on the baby’s left foot and left hand, by the priest, as a blessing and confirmation of the chosen name, after the ceremony.”

The Khasi naming ceremony is undoubtedly, the most important ritual for the people of the community and the most joyful event in a Khasi family. “A child is a divine gift and has a distinct identity and must be given a name. The birth of a newborn means the continuity of a clan. There is no bigger tragedy in the life of a Khasi than the extinction of his/her clan,” she added.

Naturally then, it is the manner of the naming ceremony that makes it unique.

Rituals

One can only imagine the excitement leading up to the baby naming ceremony; families wait with anticipation while loved ones suggest names.

The author gave an idea of the event, her description is remarkable and visual.

Sawian said, “The night before the ceremony, rice is soaked to be pounded the next morning. At the break of dawn the following morning, the rice is pounded using a thlong (pestle) and a synrei (mortar). A room facing towards the east is swept and swapped. Cane stools are placed there for the participants.”

Worship (puja) is an integral aspect of ka jer ka thoh, and commodities required for this ritual are brought in a prah, a winnowing basket. Soon, the priest comes and arranges them so they are ready for the ritual. Thereafter, parents, grandparents and all the close relatives of the newborn sit on either side of the priest. Then the baby is brought in and placed on the grandmother’s lap.

No ceremony is complete without prayers. Emphasising this, she said, “The ceremony begins with a prayer when the priest pays obeisance to U Blei (God Almighty) to bless the occasion, the maternal and paternal clans of the baby, and the name which, by His grace, will be given to the newborn.”

He proceeds to pick up the skaw or the gourd container of a solution of pounded rice and water and pours it slowly calling out the names that have been chosen.

While this ritual is completed one step at a time, those present at the ceremony watch how the solution responds to the suggested names with bated breath. Perhaps, miracles happen beyond the purview of logic.

Sawian said, “When the correct name is called out, as willed by God, the solution coagulates and forms a clot at the mouth of the skaw and miraculously sticks there. This is unique and it is always a very emotional and wondrous moment.”

Sometimes, there is anxiety, as the author highlighted. “There are times when the clot would not form and the gathering has run out of names. All of a sudden, someone would suggest a name and lo and behold, the miracle takes place. The clot forms and the baby is given his/her name.”

Confirmation

Next comes the thanksgiving prayer, a significant element in most indigenous cultures around the world where divinity resides in every day observances of gratitude.

In Khasi culture, the priests do the same to U Blei once the name is confirmed. “They beseech him to bless the child with good health and prosperity, honour and integrity so that his/her aura may be strong and glowing and the child’s life may be guided by the tenets laid down from times immemorial,” Sawian noted.

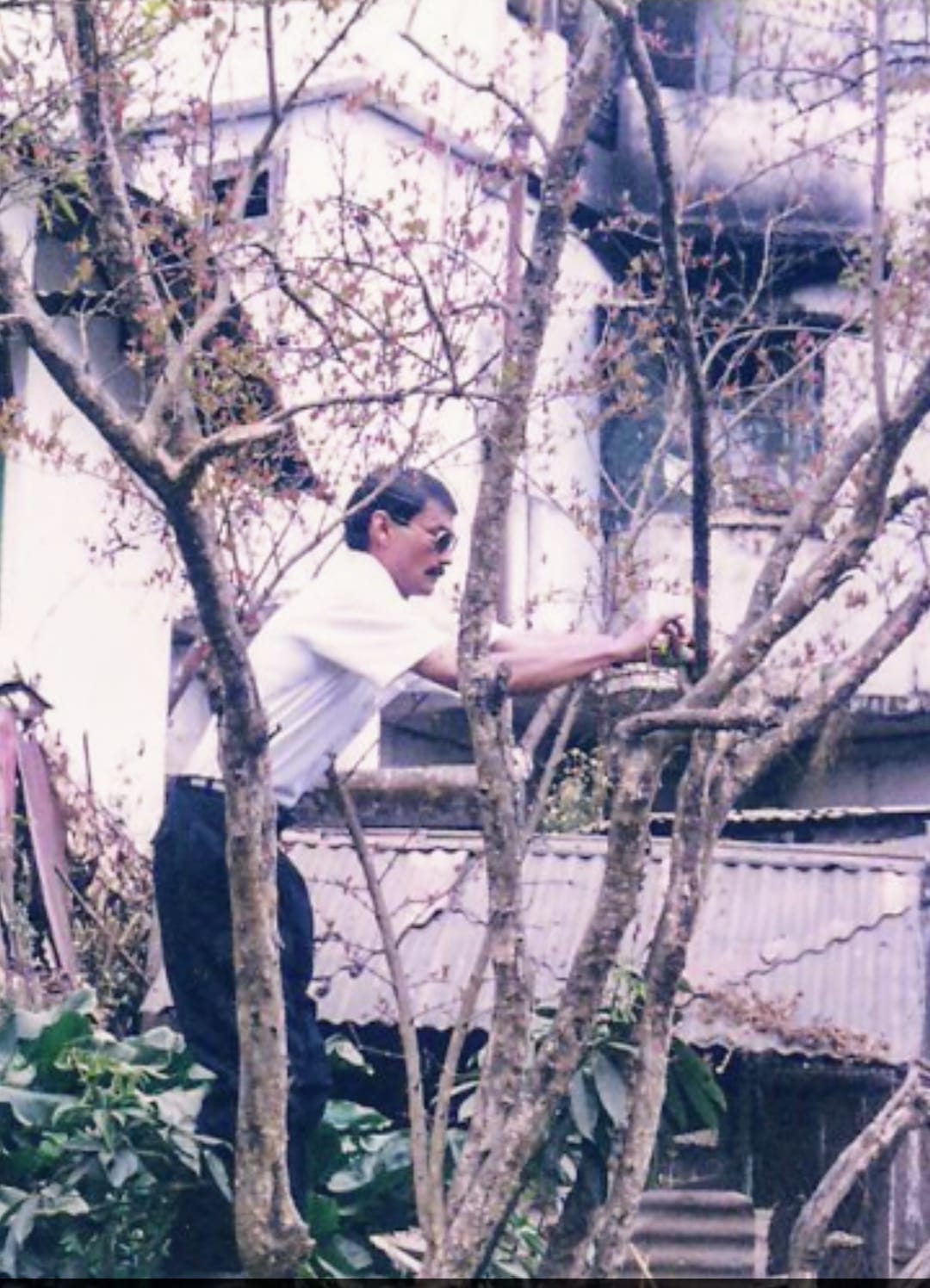

An unusual ritual of ka jer ka thoh involves the respect given to the placenta, known as jhep in Khasi. The father places it on a tree, rooted in the belief that the placenta is a protective shield, which protects the baby for nine months inside the mother’s womb, and therefore, it should not be disposed of carelessly. On the contrary, it should be treated with respectful gratitude. When the father returns (after putting the placenta on a tree) his brother-in-law pours water on his hands and feet from a brass luta (or lota).

Soon after, the baby is brought forward for the priest to smear the left foot and left hand of the child with the rice solution. This smearing is also done on the mother’s left foot and hand and on the father’s right foot and hand, including all the members on the maternal and paternal sides of the family.

An interesting facet of ka jer ka thoh involves yet another unique feature. The priest, in Sawian’s words, takes three arrows in the case of the boy child. He prays to God to bless the child with strength and fortitude. Each arrow signifies wishes related to the Khasi belief system: The first is to protect the boy; the second is for the protection of his family and clan; and the last is to protect his country.

For the girl child, the priest takes a khoh or a conical cane basket, star or the cane strap and wait bnoh or the sickle. Throughout the ritual, he explains that women are the Lukhimai (similar to Lakshmi) of a home and by virtue of this, they should be hard working, thrifty, keep the cooking fires ever glowing and the granary full.

Another thanksgiving prayer to God concludes the ceremony. Like many Khasi festivals, ka jer ka thoh is incomplete without the feast. Traditionally, only the pujer is served, sometimes mixed with sugar, and at other times savoured with freshly roasted dried fish.

Ceremonies in Modern Times

Rituals constantly evolve. Responding to the question on how the Khasi baby naming ceremony continues to transform, the author said, “The ceremony, to begin with, have slight differences in different parts of the Khasi Hills, majorly in the festivities after the ceremony. Presently, they have become elaborate and grand feasts have taken the place of the simple partaking of pujer with sha saw or red tea.”

Despite these alterations, what remains central to ka jer ka thoh is the role of the priest in the naming ceremony. Then comes the parents, who prepare the requirements for the ritual and choose the names. Both maternal and paternal sides of the newborn, friends and well-wishers come together and suggest names for the child.

The conversation steered towards indigeneity in times of technology. Sawian offered a balanced worldview. She does not think it will intrude into indigenous culture. “I personally think that technology has its own space in our lives and for a long time, it will not intrude into our culture… at least not for those who believe in a particular way of living and worshipping and they’re aware of the importance of both as being separate parts of life. Imagine if all the trees on a mountain slope are cut and replaced with a concrete jungle. How detrimental that would be for our body and soul!”

Traditions never fade away completely even as society itself grapples with technology. For Sawian, ceremonies should remain. As part of a ritual, a religious ceremony is an elevating spiritual experience no matter what faith one practices. With a smile, she said, “I attend religious ceremonies of all faiths.”

As modernity embraces the Khasi Hills within its fold, do rituals like ka jer ka thoh lose their significance?

Sharing her take on this question, Sawian explained the difference between being modern and being westernised. Perhaps, the answer lies in her personal experience. Speaking about her younger days, she said, “Being modern doesn’t mean you shed your culture. When I was young, our traditional attire and jewellery, including our turban were looked down upon by our own people. Our drums were considered ‘sounds of the Devil’. I observe the change now. As for naming one’s baby, that precious moment is an individual choice. Religion is very personal. Atheists, for instance, speak of their disbelief in God. But when you come to think of it this disbelief is their religion.”

Ka jer ka thoh is a reminder of the beauty of indigenous faiths. How long they will remain lies in the choices of future generations.