By Sainkupar Syngkli

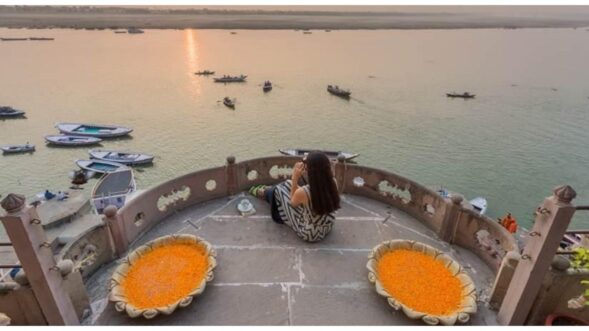

Ri Bhoi has always been known as the granary of Khasi Hills for its fertile lands. Till today, most of Ri Bhoi is covered in forest and farms, with the cultivation of rice, wheat, maize, chilli, pineapples, ginger, gourds, areca nut, rubber and Khasi mandarins, among others, making the region rich in produce. Despite how productive the land is, like many places in India, trouble brews within Ri Bhoi’s abundance.

Agricultural activity has been the life for most residents of the district and their means of earning, but as the days go by agricultural production keeps throwing up a decreasing trend; this might be the impact of climate change, the use of hybrid seeds or because of change in land use pattern with many paddy fields converted to ponds or industrial unit set up.

Back then, a rich family would be one with the largest amount of rice collected post harvest. In an effort to delve into the current scenario vis-à-vis paddy cultivation in the district, The Meghalayan visited Ronghalam, in Marngar, where most of the people focus on agriculture and the main agricultural activity is paddy cultivation.

In Ri Bhoi district, especially in the villages, people used to work in groups helping one another and the practice known as Bara Kyiad, whether it be for plantation or harvesting. The way of paddy cultivation in the district is also different from that in parts of India where paddy is planted and harvested only once a year, and the paddy they plant have its own name.

“We used to call Khaw Karow in our native language and this includes many types of paddy, with some names of these being Lahi, Synteng, Lyngkot, Mynri besides others and the taste would varu from one to another,” a farmer from Ronghalam.

The headman of Ronghalam, Stephan Ingti, narrated about the harvesting culture of the forefathers.

“Only ladies will cut the paddy and after that the men will carry it to the barn after binding it in a bunch using a bamboo that we called bhar; we call the barn I Ka Khor which is a hut made of bamboo and grass with a big open space polished with cow dug. We keep the paddy there for two to three days before we separate the rice and the hay. After three days we go and stay in our barn separating the rice the entire night, so that in the morning it will not take time. But to stay awake we work in a group and the local wine – Kyiad Um – is partaken. Everything that we do, we do in a group and we don’t feel tired.”

During the day, after the menfolk have separated the hay and the rice, the women come and clean the rice and measure it in bura each of which would contain around 30-40 kg, and once they reach home they keep most of the rice on bamboo carpet in one room, while some packets of rice within a sack are kept just above the cooking fire so that the rice becomes dry and is easy to grind in rice mill.

Harvesting is not that complex, but talking about paddy field we need to talk about the reason why it has decreased and how to improve agriculture, especially in Ri Bhoi.

Asked abou the challenges that farmers face, Ingti cited the use and impact of high yielding variety seed. “By using this type of seed we can increase the production just once, but we need to use lots of chemical fertiliser which affects the soil in the long run, therefore for us as rural farmers we always use local variety of seed which doesn’t need any chemical fertiliser to grow, all it needs is the water and the sun, Ingty said.

“People of this generation are ignoring farming and converting paddy field to pond which is something very risky because once we convert it into a pond we cannot farm in it, because the mud is different. Farming is our identity. If we lose our land, we lose our identity and our ownership of the soil. In the Bhoi community, the paddy field is our safety. Only when we have food grown in our fields do we have anything. In those years of the pandemic, many people rushed to buy food during the lockdowns. For us farmers, we felt safer because we could harvest rice and vegetables from our fields and milk and chicken from our farms”. Ingti said.

In Ri Bhoi there is also a festival to seek blessings from Goddess Lukhimai, which is organised at least once in five years, with the priest who performs the harvesting ritual praying, Ko Blei nongbuh nongthaw Ko ba seng ia ka niam ka rukom ia ki ksing ka pdiah, ka tangmuri u dhulia dhutar to nang iarap to nang ai buit to nang ai bor Ma phi ban iar ia kiei kiei baroh. Agriculture played a very vital role in Bhoi community, and through agriculture they connect with one another as a society with Bara Kyiad and help one another in cultivating and harvesting. But as the days go by and land is increasingly put to non-agricultural use Ri Bhoi is losing what was its very essence; many parts of Byrnihat area now boast of industry while Nongpoh town, which was once made up primarily paddy fields, is today a bustling market.

“I encourage other farmers to continue with agriculture and not to rush into other ventures and thus erasing the legacy of our forefathers,” Ingti said with a sigh.