By Priyanka Sana

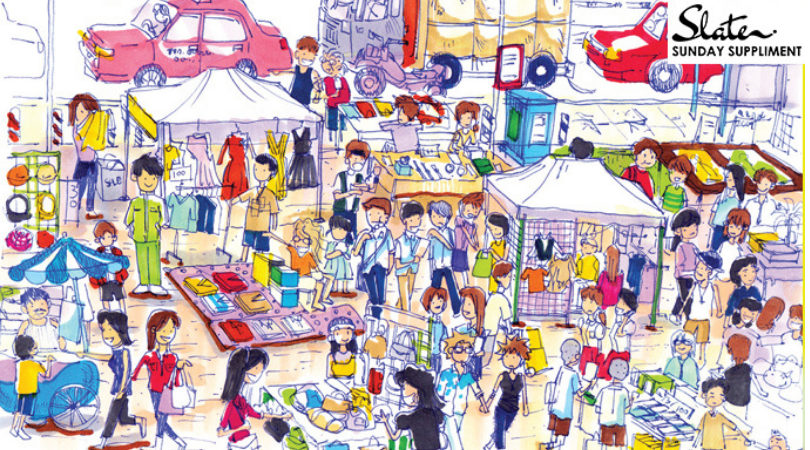

The pandemic saw a sudden boom in the number of small businesses hitting online platforms during lockdowns. People were bored, they felt the need to do something productive. And if they could also rake some profit out of it, all the better.

One of the many online businesses that have come into prominence is online thrift stores. This is particularly true for fashionable Northeastern cities such as Shillong.

Before sustainability and eco-fashion were in vogue, used-clothes stores were where people who needed to save on expenses did their shopping. The term “thrift” itself is a face-lift of the more familiar “second-hand”, a term only ever used in a derogatory sense.

The concept of thrifting, then, like all things else, is going through a transformative phase in this digital age – It has gentrified. A practice most associated with the poor has become a race to steal unique or rare pieces at heavily discounted rates – but almost free for the average middle-class customer.

The workings of class disparity are most reflective in how most online thrift items sport a steeper price tag compared with real-life markets as in Ïewduh and Laitumkhrah in Shillong or increasingly popular village markets.

Some store owners resell items from their own wardrobe in a bid to promote an “eco-friendly lifestyle” that aims to fix the fashion industry’s pollution problem. Thrifting or reusing clothes delays the inevitable journey to a landfill if people also persist from buying new clothes. But does it make financial sense to spend income on online second-hand stores when similar, much cheaper clothes are available at thrift bazaars in the city and weekday markets?

Pi Lalnhunmawii, a second-hand vendor, says, “I have been running my shop for over three years in Madantring”. Pi Mawii, as she is known, is a sport about her profession, and is delighted to run her small and independent business that she worked hard to establish from nothing.

“Even online store operators flock to the store to buy overcoats, shirts, curtains, and soft toys”, she says. But the re-pricing difference, once they reach Instagram, is illogically steep. Around these areas, the typical ask for an overcoat in season is around Rs 300 to 700, with shirts costing as low as Rs 200. Yet Pi Mawii says, “I never feel any pressure to hike the prices”. The reluctance of second-hand sellers in Shillong to raise their prices in response to online hawkers is, in effect, holding the market steady. But Pi Mawii is quick to add that this may be temporary, depending on how the culture around thrifting evolves.

Business owners around the area claim they still have high footfall, and their trade stands unscathed. Indeed, online hawkers, who cannot procure second-hand shipments and donations alone, are amongst their many customers. Some even operate online extensions of their physical store. But shoppers still like to “hunt” for quality pieces themselves than rely on photographs online, say, business owners.

A casual chat with young students in Shillong revealed that most agreed online hawkers were unjustifiably inflating prices. Prices more than double as you move from Motphran to Instagram. Online hawkers say the re-price reflects their effort to find these pieces, but few have broached the subject of these businesses raking in an untaxed profit by exploiting working-class trade.

Online thrift shops, however, also fill a gap in the market. Many people prefer second-hand clothes, but do not have the time to sift through them. Shopping from online hawkers is simply easier, cheaper than buying new clothes and can cater specifically to unique styles. Every online hawker has a unique wardrobe style, and each competes with providing a clean service, from using compostable packing to writing hand-written notes.

There will always be shoppers who would want to drop by at a second-hand market. While we cannot ascertain the exact future trajectory of growth in the world of used clothes and accessories, for now, the trend is growing popularity westward, with young, well-off women starting thrift shops on Instagram in metropolitan cities, where taboos against class-mixing are stronger and the word “second-hand” is seen as offensive. For now, the brick-and-mortar shops, bazaars and village markets are holding ground.