By Eleanor A. Sangma

The old gods and goddesses lived amidst nature. Although nameless and formless, they could be found in the cool waters of rivers and lakes, the rich greens of our hills and mountains, and in the creaking branches and rustling leaves.

Of the celestials, the sun, the moon and the stars were also said to be associated with gods and goddesses, powerful and immortal. One such god is called Misi Saljong, one of the greatest in the pantheon of A·chik deities.

It is said he was all-giving, ruler of the sun sphere and all things that bloom and grow. Lovers of classics might find a near equivalent in the sun god Apollo of the Greeks, with attributes of the goddess Demeter.

Stories tell us that our forefathers were initially wanderers, living on what the land and seasons provided. Taro and herbs were their go-to food. It was Misi Saljong who blessed them with rice seeds, taught them how to be more attuned to seasons and grow their own food with the help of the rain goddess and the fire god. Till today, the Garos remain a majorly agrarian community.

Sometimes his love came coloured with pain, sometimes accompanied by death. In order to appease the deity, believers – who are known as Songsareks – would perform rituals and offer sacrifices in his name.

The festival of Wangala is an offering to Misi Saljong, making it the biggest festival of the tribe associated with the jhum cycle. Observed by the Songsareks who remain scattered in small rural pockets of Garo Hills, the celebrations aim to express gratitude for a bountiful harvest and to seek god’s blessing for the coming cycles.

Before the annual harvest festival, several religious ceremonies are observed over the course of the year. This is done in order to ensure harmony with deities and spirits who reign over agricultural seasons. Some of these are O.pata ceremony where the omens are consulted through dreams before clearing and cultivating a plot of land; Den.bilsia festival, which is celebrated after the clearing of the land is completed; Agalmaka is performed to seek the blessing of deities after burning of new jhum fields; Rongchu gala, involves the offering of the first fruits to Misi Saljong.

As the sun sets on the evening of the predetermined date for Wangala, the rituals start with worship and sacrifices to various deities and spirits such as Rongdik Mite (goddess of wealth), Nokni Mite (spirit of the house), Krongna Do.tata (sacrifice to the sacred post), Kram Do.tata (sacrifice to the sacred drum), Nagra Do.tata (sacrifice to flat drum), Ang.ke Do.tata (sacrifice to the crab) and A.kom, Miwa Do.tata (sacrifice to the gong and the bell).

After this, the official ceremony of (Chu) Rugala takes place at the Nokma’s (village Chief) house. To the accompaniment of the traditional drums, gongs, and other instruments, traditional rice beer is poured out as an offering to the sun god. The liquor and all the crops harvested are first offered to the deity before they can be consumed by people. This is followed by Wanti toka, where paste made from rice is used to decorate all the houses in the village, leaving behind a canvas of white handprints.

The villagers will then gather again at the Nokma’s house for the Sasat so.a ceremony, which refers to the burning of incense obtained from the Sasat tree.

The Sasat is an important aspect of Wangala, according to our forefathers; it was the first tree to ever be shaped by our maker. The smoke will go out along the Maljuri (the main post of the house). Some interpretations say that if it goes out smoothly without smoking up the whole house, it signifies blessings of the gods and a good harvest for the following cycle.

After the first Wangala dance at the Nokma’s house, every house will host guests with food and rice beer. They will dance with gods and men for several nights. The uninterrupted celebrations also provide an opportunity for young men and women to choose their life partners.

The closing ceremony is known as Rusrota, which is observed to ensure that the crops are kept safe in the granaries.

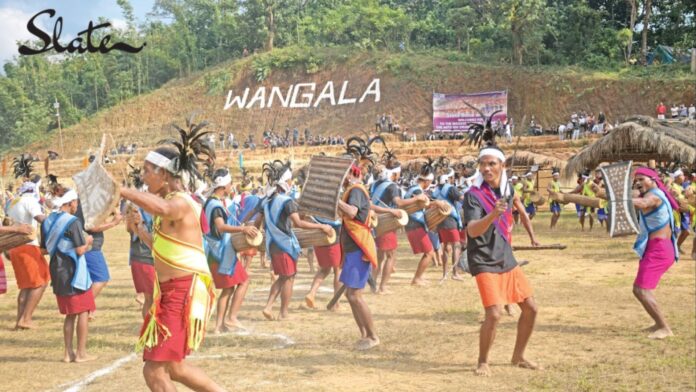

The Wangala dance has different formations that represent different stages of cultivation and also depict the everyday life of the people. Some of these formations mimic how nature and its elements move – the sway of trees and the dance of birds and animals. Do.kru sua depicts two doves – believed to be humans once – pecking at each other; chambil moa, represents the pomelo fruit; makkre rika shows the act of chasing away monkeys and other animals that harm crops.

The Dama (the traditional drum) and the Adil (a buffalo-horn trumpet) constitute the signature sounds of Wangala, among others.

Some of these instruments, stored in a separate nokpante (bachelor’s house), have memories and stories attached to them. The Kram is a sacred drum that is larger on one side and tapering away towards the other end. It is said that a deity has made its home in it and other than the Nokma whose house it is kept in, no one else can touch the drum.

The Rang, or gong, refers to brass or metal plates, which are also used to produce sounds. It was a symbol of wealth and a deciding factor in one’s social standing.

While the authentic rituals are observed only by the Songsareks, the Wangala dance has been part of the mainstream population for years. Even amongst most Christian Garos, the dance is presented in many cultural events and gatherings.

As students, we had to practice the dance for months before our annual inter-house Wangala competition that was held every year in school. I still remember the excitement palpable in the fast-approaching autumn air, the clang of sanggong (traditional bangles) and the swish of do.me (feathered headgear) as students prepared for the dance.

The rest of the world learns about it through the 100 Drums Wangala Festival held in November each year. It has become symbolic of the Garo identity, with the colourful attire and the rhythm of the drums being recognised on national and international levels.

The festival derives its name from the 10 dancing troupes participating in the yearly competition, each having 10 drummers with a cumulative total of 100 drums.

“It started with only 10 drums in 1976 at Chandmari field in Tura,” Rakkan M Sangma, Joint Secretary of 100 Drums Wangala Committee, said.

“When Captain Williamson A. Sangma, our first Chief Minister, came and attended the initial celebration in June, he asked why only 10 drums, why not 100? So, on December 6-7 of the same year, the first 100 Drums Wangala was organised at Asanang,” he explained.

Since its inception, it was never meant to be an exact replica of the Songsarek rituals. It was started to preserve and promote our traditional dance and culture; hence, the point is not to observe the full rites. In that aspect, the festival has not witnessed much change.

“If we talk about changes, there seems to be less interest amongst the current generation. Even people from the villages don’t seem to be much keen on it in recent years,” Rakkan said, adding that people from Germany, Netherlands, America, and other countries have come and educated themselves about “our culture. In contrast, our own people are the ones lagging.”

“This is a major worry for us, as it’ll prove to be a threat to the Garo community,” he highlighted.

A·chik culture consists of myriad memories passed down by our forefathers, some of which live on till today. Yet, our culture is also made of dying languages, unseen forms of poetry and art, and forgotten stories.

This year has been a major learning experience for me. Going back to my roots and exploring the lesser-known (along with the well-known) aspects of our culture. Spending months diving through them, the words of an indigenous writer, Linda Hogan, kept me company on my journey. It goes, “Suddenly all my ancestors are behind me. Be still, they say. Watch and listen. You are the result of the love of thousands.”