Is she a terrorist? Is she from the underworld? Are you a member of the Chhota Rajan gang?”

Numerous questions and one answer: NO.

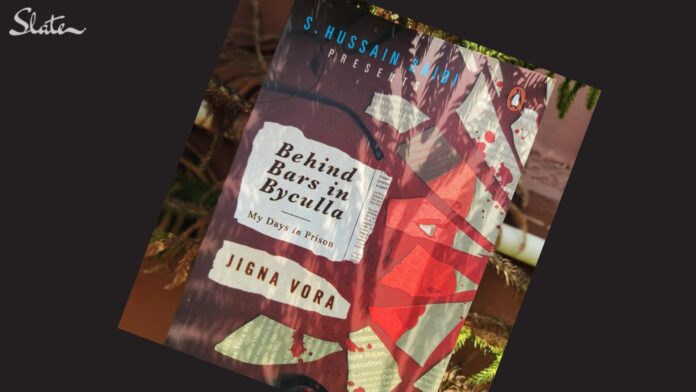

Hard-hitting reality, spine-chilling, excruciatingly terrifying – encapsulate Jigna Vora’s Behind Bars in Byculla (2019) – a gripping jail memoir, which is all set to thrill the audience with a new web series Scoop, helmed by filmmaker Hansal Mehta.

A story of hope and injustice; of pointlessly living behind bars; of loss and politics; of fighting for one’s rights… the author leads the readers through her painful journey of getting arrested and then acquitted.

While the 2011 murder case of renowned journalist Jyotirmoy Dey captivated curious eyes, little was known of Vora, a woman journalist who was taken into police custody for allegedly instigating the murder, in collaboration with the underworld.

She was accused of e-mailing details about Dey to the mafia, Chhota Rajan himself.

She pleaded not guilty; requested and begged, nonetheless, the tag of “Accused no. 11” was designated to her. Vora was flanked inside Byculla Jail in 2011, where she came face-to-face with bouts of depression and anxiety, including, the harsh realities of life and of being an accused in an incognizant crime.

Vora unknowingly and perhaps, involuntarily ended up with people she once reported about. Karma, they say.

What happens behind bars is rather thought-provoking, however, we become a bunch of know-nothings when it comes to the misery inmates experience.

Well, here’s the plot twist – as she leads one through her days in prison, she helps readers get slightly accustomed to the humiliation faced, especially being held in a crime one hasn’t committed. On her admission day, a menstruating Vora had to strip totally naked, despite begging the lady constables to spare her underwear.

What was to follow for a lady who lived life on her own terms and had a 12-year-old son waiting for her at home was more humiliation, a stained reputation, and one recurring thought – “What will people think?”

Indescribably traumatic as it is, Vora opens up about her troubled childhood, sharing how her alcoholic carefree father visited her in prison for money. “Give me some money. I can come to visit you every day. You are my daughter.”

Booked under the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act (MCOCA), her life had taken a tumultuous turn, but the author displays a series of events where, albeit discovering hair strands in dal and worms in food, a stained toilet, abusive inmates, and influential women, she stood her ground, waiting to hear the words “Jigna Vora is acquitted,” which she did, in 2018.

With a successful journalistic career, Vora has in this novel, traced her journey as a crime reporter and how she rose to achieve an identity, a good name in the industry, breaking numerous front-page stories, for instance, on Jaya Chheda, whom destiny has it, she met in jail, and Abu Salem, Monika Bedi where Vora, with her brilliant skills, got her hands on love letters Bedi wrote to Salem from jail.

Her interaction with the saffron lady Pragya Singh Thakur – main accused in the 2008 Malegaon blasts – adds more spectacle of how the insignificant and influential alike, lead the same life on becoming convicts.

Thakur, however, Vora describes as a spiritual person. “People write a lot of things. Not all of it may be true.”

Sitting in the comfort of our homes, us readers can only comment on absurdities of the many accused serving their time inside a cell, “They are bad people,” we willingly comment, however, not all of them are bad, are they?

Some succumb to legitimate helplessness. Vora underlines this fact through a conversation with a lady who risked a jail term for mere 500 dollars. “In my country 500 dollars is a lot of money actually. We are so poor that some girls don’t get food to eat, and they have to solicit customers for as little as two or three dollars,” the lady explains, further adding, “Jail is better than home. We get three meals a day here. And this place is more hygienic.”

Behind Bars in Byculla effortlessly spins a tale of how one can accomplish great heights in their profession and be brought down because of the same profession.

Vora describes how acquaintances and friends who once nodded in agreement, now thrusted cameras and mics into her face, “You have been arrested for the murder of J. Dey. What do you want to say?”

The memoir definitely comes across as an eye-opener but also leaves one pondering about the flaws in our judiciary.

Vora, a mere suspect, was wrongly accused and sent behind bars ripping her off of her dignity and self-esteem. However, while she is acquitted, the book leaves behind not just questions of the instigator behind her involvement, but a solemn contemplation, a dreadful silence and maybe reassurance that truth aways wins!