By Adity Choudhury

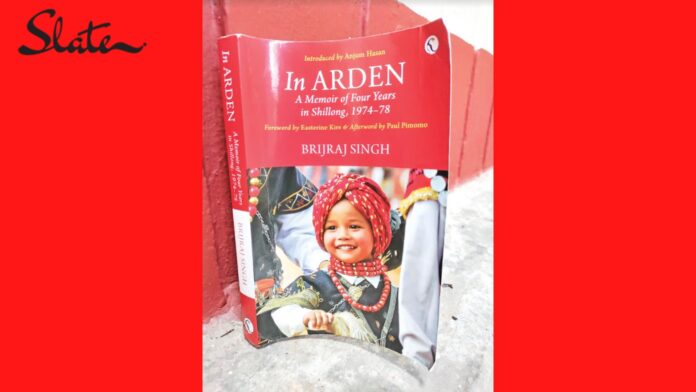

It takes tremendous courage to write about a society in transition. In Arden: A Memoir of Four Years in Shillong, 1974-78 by Brijraj Singh is one such book.

His observations are precise… both its strength and weakness in terms of polarising readers. Not everyone will agree with his thoughts. Some may even get offended.

At once astute in his observations and humorous, this ‘seemingly’ simple book details the author’s stay in Shillong from 1974 to 78.

But first, let’s meet the author. A distinguished professor, among others, he is a Rhodes scholar at Lincoln College, Oxford, and a Fulbright Fellow at Yale University; he was awarded his doctorate at Yale. Taken in context, one can see that in its formative years, North Eastern Hill University (NEHU) saw and ensured the teaching staff was vibrant and progressive. The Singhs were faculty in the Department of English.

This book is not only fearlessly critical about the university but offers an insightful glimpse of the place through internal politics, detailed in the eye-opening chapter, “Work”.

Divided into seven thematic chapters, the author gives intimate details of a city, he briefly called home. The title of the book is a reference to William Shakespeare’s celebrated comedy, As You Like It.

With a foreword and introduction by Easterine Kire and Anjum Hasan, respectively, we will travel through time. The afterword by Paul Pimomo emphasises the author’s empathy and reflection, which marks the writing.

In the preface to the book, Brijraj gives readers a glimpse into his mind. The first five chapters were written “in a couple of months” shortly after they left the city. Following a gap of decades, he completed the manuscript.

The first chapter, “Getting There” is, as the title suggests, about reaching Shillong. Hilarious and conversational in its tone, the chapter details the journey from New Delhi. The rush of the Indian railways is palpable. We follow him as he follows the porters, carrying luggage from one train to another.

Singh also focuses on the stereotype – Shillong is as exotic as Ceylon. This may be relatable to young students who leave the North East region for higher studies in bigger cities. How many times have you been asked if you’re from Ceylon?

Here’s a snippet of conversations when The Singhs announced their departure from New Delhi:

“Meghalaya is in Assam.” “Isn’t that Nagaland?” “Is that where they eat rats?”

“Nay who? she answered, neigh hoo? What is that? And before I could reply, she added, ‘Sounds like an ass braying. Are you sure you’ll like it, whatever it is?’”

It is in this chapter that we meet their pet cat, called ‘Cat’, who, in his curious way, leaves an impression. Going against his nature, he finds rats disgusting.

We also meet CDS Devanesen, the vice chancellor of NEHU. Through him, we get a glimpse of the new university. In the words of the author, “NEHU was to be the brave new academic world of the future, and he, like Moses, was to lead us to it.”

Later, his human frailties come to light.

The next chapter, “Living There” begins with the author’s wife, Frances, being admitted to the Welsh Presbyterian Hospital; she comes down with jaundice. To escape the depressing atmosphere, he ventures out and discovers a known name, R. B. Stores.

Following her recovery, the couple decides they need better accommodation. Enter Mr. C.S. Booth, who, after interviewing them, offers a house on rent. Reading the chapter, “Respice”, one gets an idea about the lineage of this former Deputy Commissioner of the Khasi Hills.

A paragraph in the chapter reads, “He used to say that his ancestor was an Englishman, and that he had American connections too. When we were in Salt Lake City once in the early 1990s, Frances ascertained from the great genealogical records of the Mormons that the family of the Booths was indeed a British family, one branch of which migrated to the United States, and produced both the famous Shakespearean actor Edwin Booth and the notorious assassin of President Abraham Lincoln, John Wilkes Booth. Another scion of the family came to India as a soldier. Originally stationed in the plains of what is now Uttar Pradesh, he moved east with the army and ended his career in Assam where he married a Prussian lady. Mr. Booth was a descendant.”

Mr Booth possesses the Englishman’s charms and working ethics. Always available at their service, it is through him that they get to know Shillong. Not surprisingly, however, the house they stay at is supposedly haunted. Very quickly, the author realises that the people equate Mr Booth with bhoot, hence, the term, bhoot ghar.

Readers are left amused at the quirks of language.

Brijraj also speaks about the Khasi love for cleanliness, Khasi squash, orchids, and other species of flowers. We also meet several worldly wise street dogs – Charity and Lion – and Romper, who lived with them, a gift from one of their neighbours.

A sense of warmth permeates through the pages of the book. Here, they name their house, “Arden”, true to their love for the bard.

In the chapter, “Friends”, we meet a motley crew of people. From here on, readers will observe the author’s sharp, precise, insights into the people.

The Duaras, civil servants like Nari Rustomji and his family, the Jaffas, Swarup Mukherjee, Mr. Richmond, and then Governor, L.P Singh, Prof. Noorul Hasan, and Mr. Thorose, among others – they come from elite families – and despite this, priviledge is balanced out with a deeper concern for the city and its people.

It is also in this chapter that we see that all is not well in the grand vision that is NEHU, amply clear in the book.

The Singhs ruled out friendships with people from the university; the author admits they could not mingle freely with the educated, middle-class Khasis. That said, those who come from a variety of professions, alter the author’s opinions, somewhat – the office clerk, the kongs, and the vegetable seller, to name a few.

One needs to take the chapters, “The Place” and “The People” with a pinch of salt, keeping in mind, two things: he writes about the city of the 1970s and Shillong has changed; the youth is playing its role in ushering positive changes. Readers will realise how the past shapes and informs the future.

Khasi names fascinate the author – kongs Between and Berate, the driver who named his children, First Gear, Second Gear, Third Gear and Accident (thankfully, not Neutral), Controlled Rate and Augustborn.

In the last chapter, “Respice”, the author updates us on the people he mingled with; many have passed on. It ends with the author writing that The Singhs now “lead quiet, content lives in a secluded part of New York City and are happy.”

Brijraj provides an intimate glimpse of a newly carved out state, which meant challenges – he addresses them and alternately muses about the ways they can be countered.

His observations may leave some readers angry. Reading through the book, one can sense that Brijraj is aware of this, yet is ‘blunt’ in his observations.

The book feels like postcards from the past, yellowed with time. For the 21st-century Shillongite, sepia-tinged characters will greet us, as we smile at them.